About Public Health England

Public Health England exists to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. We do this through world-class science, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships and the delivery of specialist public health services. We are an executive agency of the Department of Health, and are a distinct delivery organisation with operational autonomy to advise and support government, local authorities and the NHS in a professionally independent manner.

Public Health England Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG Tel: 020 7654 8000 www.gov.uk/phe Twitter: @PHE_uk

Facebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEngland

This briefing was written for PHE by the HBSC England Team; Professor Fiona Brooks, Kayleigh Chester, Dr Ellen Klemera and Dr Josefine Magnusson.

© Crown copyright 2017

You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit OGL or email psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright

holders concerned. Published June 2017

Contents

About Public Health England 2

Executive summary 4

Introduction 6

Key findings 7

Conclusion 16

Resources and further information 17

Appendices 20

Executive summary

This report summarises data on self-harm informed by an analysis of data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey for England, 2014.1 The data draws on responses from 5,335 students aged 11-15 years who completed the HBSC survey in England.

This thematic report presents data from the most recent survey and illustrates

associations between self-harm and demographics and social context. Relationships of importance and relevance which demonstrate considerable differences have been reported – guided by previous work on HBSC which has mapped protective factors across individual, family, school and local community domains.

This report is one of a series of three, the others covering cyberbullying and the wellbeing of adolescent girls.

This report is intended for a range of audiences interested in promoting children and young people’s mental wellbeing, including for example: local public health specialists, school nurses, head teachers and college principals, CCG leads, local councillors, CAMHS leads, mental health strategic clinical networks and local children and young people’s mental health commissioners.

Key points:

22% of 15 year olds reported that they had ever self-harmed

nearly three times as many girls as boys reported that they had self-harmed (32% of girls compared to 11% of boys)

the comparison between recent HBSC England findings and earlier studies2,3

suggests that over the past decade rates of self-harm have been increasing among adolescents

HBSC findings indicated that the likelihood of self-harming varied by social-economic status and structure of households, the incidence of self-harming is associated with lower family affluence (Table 1, Figure 1)

Introduction

oductio

Self-harm is an intentional injury to one’s own body resulting in tissue damage.4 Self-harm can include actions such as cutting, burning, biting oneself, ingesting toxic substances as well as a wider breadth of self-harming behaviours. The behaviour is predominantly a feature of the adolescent population, but not exclusively, and is more common among girls than boys.2 Acts of deliberate self-harm are strongly associated with emotional distress and mental health issues and the behaviour is often described as being accompanied by a complex set of negative feelings, such as self-loathing, disgust and shame.5

Those who self-harm in mid-late adolescence potentially face increased risk of

developing mental health issues, as well as higher prevalence rates across a range of health risk behaviours in late adolescence and early adulthood; including increased likelihood of suicidal thoughts. 6

Data source - the HBSC survey

HBSC is a survey-based study conducted in collaboration with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. The survey examines the health and wellbeing, health behaviours and social environment of young people aged 11, 13 and 15 years in countries across Europe and North America.7 For further details see Appendix 1.

Key findings

Prevalence

Self-harm is a sensitive topic with potentially high levels of underreporting2 and as a result accurate prevalence figures are difficult to determine precisely. Internationally, for OECD countries reports tend to indicate about 13%-18% of adolescents experience a lifetime risk of self-harm 8 with prevalence rates having increased across the last decade in many countries.

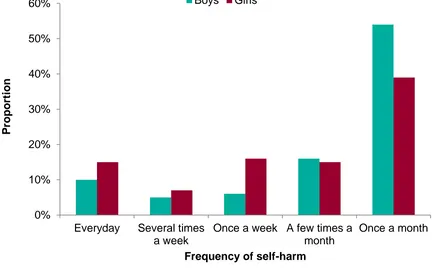

[image:7.595.47.486.405.676.2]The majority of people who self-reported self-harm are aged between 11 and 25 years, however, self-harming behaviours are most likely to occur between the ages of 12 and 15 years.2 The HBSC Study identified prevalence rates at 22% for 15 year olds in England. Nearly three times as many girls as boys reported that they had self-harmed, 11% of boys compared to 32% of girls. The majority of those young people who were self-harming reported engaging in self-harm once a month or more.

Figure 1. Frequency of reported self-harm among 15 year olds by gender

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1 0%

10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Everyday Several times a week

Once a week A few times a month

Once a month

P

ropo

rt

ion

Frequency of self-harm

Self-harm and Inequalities

Prevalence by Family Affluence (FAS) and free school meals

Self-harm has been linked with family affluence and socio-economic status.2In the recent HBSC survey, the likelihood of self-harming varied by socio-economic status (SES), as measured by the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) and receipt of free school meals (FSM). The FAS was designed as a proxy measure of SES suitable for young people and categorises them as low, medium and high FAS.1The incidence of self-harming is associated with lower family affluence (Table 1).Similarly, young people receiving free school meals were more likely to report self-harming behaviour (29% girls and 21% boys who were in receipt of free school meals across all ages reported ever having self-harmed).

Table 1. Prevalence of self-harm by gender and family affluence scale (FAS)

FAS category Proportion of young people

Boys Girls Total

Low 18% 41% 30%

Medium 10% 34% 25%

High 10% 25% 18%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Association of self-harm with life satisfaction

The HBSC study includes data on life satisfaction, allowing for comparisons with self-harm. Life satisfaction was measured using the Cantril Ladder,9 where young people were asked to pick a number from 0 (worst possible life) to 10 (best possible life) presented as steps on a ladder. The following cut-off points were applied to the life satisfaction data:

0 to 4 = ‘suffering’ - low life satisfaction

5 to 6 = ‘struggling’ - medium life satisfaction 7 to 10 = ‘thriving’ - high life satisfaction

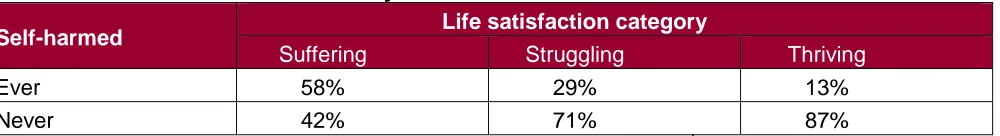

Young people who reported ever self-harming were more likely to be classed as

‘suffering’ compared to those who reported never having self-harmed (Table 2). Equally, young people who had never self-harmed were more likely to be classed as ‘thriving’ or ‘struggling’ than their peers who had reported self-harming during their life time.

1

Table 2. Prevalence of self-harm by life satisfaction

Self-harmed Life satisfaction category

Suffering Struggling Thriving

Ever 58% 29% 13%

Never 42% 71% 87%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Family

The HBSC study explores the perspectives of young people on the multiple

environments of their lives including their relationships with family and peers, thereby enabling the possibility to explore the relationships between social factors and self-harm. Analysis highlighted that the family may play an especially important role in relation to self-harming behaviours.

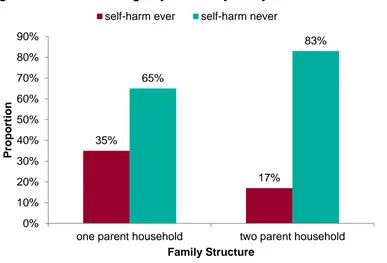

Family structure

Figure 2. Self-harm among 15 year olds by family structure

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Communication with parents

Positive family relationships are strongly associated with positive health and wellbeing during adolescence.10 Family communication represents a protective factor for positive development in adolescence. Recent investigations have stressed the importance of good communication with parents for better health and social outcomes in

adolescence.11 The HBSC England study asked young people about family dynamics, including how easy it is to communicate with parents. Young people who had ever reported self-harm were more likely to report difficult communication with both their mother and father, compared to those who said it was easy to talk to their parents (Table 3). Parents may therefore play an important role in protecting young people from self-harming; those reporting easy communication with their parents were less likely to report that they also self-harmed than those who found it more difficult to talk to their parents.12

Table 3. Young people having ever self-harmed, by ease of communication with parents

Communication with

Proportion of young people who found communication

Easy Difficult

Mother 15% 44%

Father 11% 36%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Young people who felt that important things were discussed in their family, and that someone listened to them when they spoke, were less likely to report having ever self-harmed (Table 4). Also, young people who reported ever having self-self-harmed were less

35% 17% 65% 83% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

one parent household two parent household

P

ropo

rt

ion

Family Structure

likely to say that they receive emotional support from their parents, and less likely to say that they have someone in their families to share their problems with (Table 4).

Table 4. Young people who have ever self-harmed, by family support

Family support

Proportion of young people

Agree

Neither agree

nor disagree

Disagree

Get emotional support

from family 14% 26% 37%

Talking important 14% 30% 51%

Having someone in family

who always listens to you 15% 52% 32%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Learning environment

The school environment is strongly associated with adolescents’ health and wellbeing,13 in particular, emotional wellbeing.

Table 5. Perception of school environment by self-harm involvement

Perception of school environment

Self-harmed

Proportion of young people

Agree

Neither agree

nor

disagree

Disagree

“I feel safe in this school”

Ever 17% 34% 49%

Never 83% 66% 51%

“I feel like I belong in this school”

Ever 15% 30% 50%

Never 85% 70% 50%

“I feel that my teachers care about me as a person”

Ever 15% 27% 46%

Never 85% 73% 54%

“I feel there is a lot of trust in my teachers”

Ever 14% 25% 41%

Never 86% 75% 59%

Liking school

Young people who reported that they had self-harmed were less likely to report liking school than those who had never self-harmed (Figure 3). Young people who reported ever self-harming were three times more likely to report ‘not liking school at all’, compared to those who have never self-harmed (19% v. 6%).

Figure 3. Having ever self-harmed by liking school

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE)

The HBSC England survey investigates attitudes and beliefs regarding personal, social, health and economic education lessons (PSHE), provided by most schools in the UK. Young people were asked about the provision of PSHE education at their school, including their perception of how well PSHE lessons cover a number of topics outlined by Ofsted.14 Of those who reported receiving PSHE education, a higher proportion of young people who said the topic of personal and social skills were poorly covered during PSHE education reported experiencing self-harm, compared with those who felt the topic had been well covered at school (Table 6). Examination of HBSC England data suggests PSHE education may function as a protective asset by fostering positive relationships within the school environment.15

10% 43% 29% 19% 21% 56% 18% 6% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Like a school a lot Like a school a bit Don't like a school very much

Don't like a school at all P ropo rt ion Like school

Table 6. Perception of PSHE education provision by self-harming involvement

Self-harmed

Proportions of young people who said Personal and Social Skills covered

Well in PSHE Poorly in PSHE

Ever 20% 32%

Never 80% 68%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

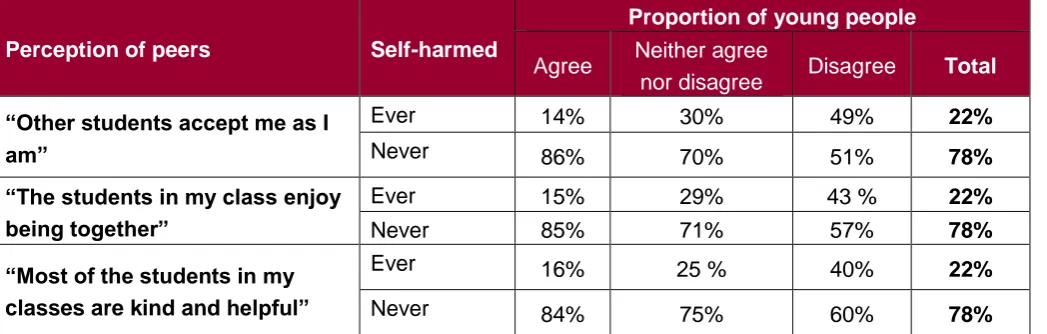

Peers

Peers are sometimes perceived negatively in relation to self-harming behaviours, especially with regard to concerns about possible associations with peer pressure. HBSC data did identify that young people who demonstrated positive perceptions about their relationships with their school peers and classmates also reported lower levels of self-harming (Table 7).

Table 7. Perception of peers by self-harm involvement

Perception of peers Self-harmed

Proportion of young people

Agree Neither agree

nor disagree Disagree Total

“Other students accept me as I am”

Ever 14% 30% 49% 22%

Never 86% 70% 51% 78%

“The students in my class enjoy being together”

Ever 15% 29% 43 % 22%

Never 85% 71% 57% 78%

“Most of the students in my classes are kind and helpful”

Ever 16% 25 % 40% 22%

Never 84% 75% 60% 78%

Source: WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2014 survey 1

Association of self-harm with being bullied

The HBSC study for England includes data on bullying and cyberbullying22 allowing for comparisons against self-harm behaviour. The experience of bullying victimisation (including traditional bullying and cyberbullying)2 is associated with experiencing and expressing

emotional distress, hence it was important to examine if there were associations between bullying victimisation and self-harm. Among young people who reported ever self-harming about half reported that they had been bullied over the last two months, 49% reported experiencing traditional forms of bullying and 32% reported experiencing cyberbullying by messages. Among young people who reported never self-harming, about 24% reported experiencing traditional forms of bullying and 11% reported experiencing cyberbullying by messages.

2

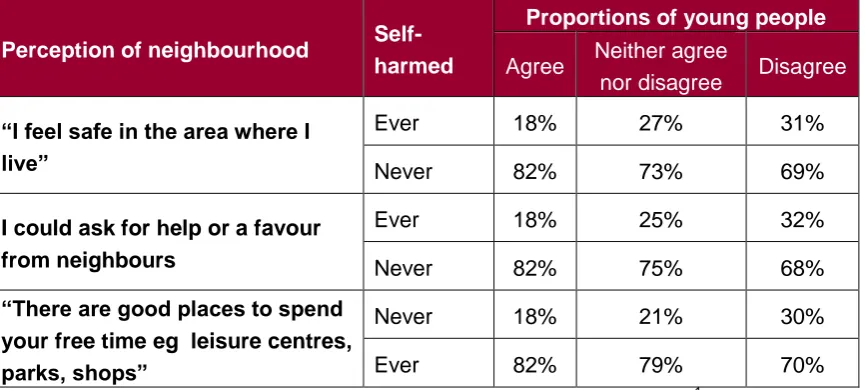

Community

Research has demonstrated the community environment where young people live can have a significant impact on health and wellbeing, especially as young people transition from childhood to more unsupervised time in their communities.16 The HBSC England study asked young people whether they agree or disagree with a number of statements about their neighbourhood. Young people with a positive perception of their

[image:15.595.42.475.532.727.2]neighbourhood (including issues relating to feeling safe in their community, having positive relationships with neighbours and having good places for young people to go in their community) were less likely to report having self-harmed compared with those who held negative opinions about how supportive and safe they perceived their community to be8).

Table 8. Perception of neighbourhood by self-harm involvement

Perception of neighbourhood Self-harmed

Proportions of young people

Agree Neither agree

nor disagree Disagree

“I feel safe in the area where I live”

Ever 18% 27% 31%

Never 82% 73% 69%

I could ask for help or a favour from neighbours

Ever 18% 25% 32%

Never 82% 75% 68%

“There are good places to spend your free time eg leisure centres, parks, shops”

Never 18% 21% 30%

Ever 82% 79% 70%

Conclusion

o he

The information in this report demonstrates that a significant proportion of 15 year olds in the HBSC 2013/14 survey had engaged in self-harm. Nearly three times as many girls as boys reported that they had ever self-harmed. The significance of gender

difference in self-harm in this age group is important for health education, family support and social care professionals to understand in developing a response to the issue. The protective nature of adolescents’ multiple environments (family, learning environment and wider community) can help to inform strategies to prevent self-harming behaviour among adolescents.

Resources

and further

Resources and further information

Public Health England (PHE)

Improving young people’s health and wellbeing: A framework for public health

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/399391/20150128_YP_ HW_Framework_FINAL_WP__3_.pdf

Measuring and monitoring children and young people’s mental wellbeing: A toolkit for schools and colleges

www.annafreud.org/media/4612/mwb-toolki-final-draft-4.pdf

Children's and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Profiles: a data tool on risk, prevalence and the range of health, social care and education services that support children with, or vulnerable to, mental illness

fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/cypmh

Child and adolescent mental health services needs assessments and service snapshots for local authorities and CCGs

atlas.chimat.org.uk/IAS/profiles/aboutdynamicreports

Protecting children and young people’s emotional health and wellbeing: A whole school and college approach

cypmhc.org.uk/sites/cypmhc.org.uk/files/Promoting%20CYP%20Emotional%20Health%20and %20Wellbeing%20Whole%20School%20Approach.pdf

Public Health England’s National Child and Maternal Health Intelligence Network produce a number of eBulletins on Child and Maternal Health which you can sign up to

public.govdelivery.com/accounts/UKHPA/subscribers/new

Rise Above

Department for Education (DfE)

Longitudinal study of young people in England cohort 2: health and wellbeing at wave 2 www.gov.uk/government/publications/longitudinal-study-of-young-people-in-england-cohort-2-wave-2

The Children’s Society

The good childhood report 2016

www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/pcr090_mainreport_web.pdf

MindEd

MindEd is a free educational resource on children and young people’s mental health for adults www.minded.org.uk/

Association for Young People’s Health (AYPH)

A public health approach to promoting young people’s resilience: A guide to resources for policy makers, commissioners, and service planners and providers

www.youngpeopleshealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/resilience-resource-15-march-version.pdf

Young Minds

Resources for children, young people, parents and professionals on emotional wellbeing and mental health of children and young people.

www.youngminds.org.uk/

YoungMinds have a range of available resources for young people, parents and professionals on self-harm

www.youngminds.org.uk/noharmdone

National Children’s Bureau

Gender and children and young people’s emotional and mental health: manifestations and responses: A rapid review of the evidence

PSHE Association

Key standards in teaching about body image. Guidance on teaching about body image as part of the PSHE curriculum

www.pshe-association.org.uk/curriculum-and-resources/resources/key-standards-teaching-about-body-image

Guidance on preparing to teach about mental health and emotional wellbeing

www.pshe-association.org.uk/curriculum-and-resources/resources/guidance-preparing-teach-about-mental-health-and

Childline

Information and support on self-harm

www.childline.org.uk/info-advice/your-feelings/self-harm/

Mind

Information on possible causes of self-harm and how to access treatment and support

www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/self-harm/#.WI9qG1WLTs1

See Me

A film and lesson plan resource pack for teachers and other practitioners working with young people to tackle the myths that surround self-harm, reduce stigma and reduce barriers to seeking help

www.seemescotland.org/media/6804/onedgepack02.pdf

University of Oxford

A guide for parents and carers who have discovered a young person's self-harm

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1: The HBSC survey

The survey is administered to a nationally representative sample of young people in each country. HBSC is repeated every four years allowing for temporal trends in young people’s health and wellbeing to be examined.

In 2013/14, a random sample of English secondary schools, stratified by region and school type (independent and state), resulted in a sample size of 5,335 students. The HBSC survey includes questions from different domains of a young person’s life, for example; family communication, teacher relationships, perception of school

environment and feelings of safety. For more information about the HBSC study see www.hbsc.org

Appendix 2: HSBC measure of self-harm

The measure used to assess self-harm was as follows:

1 “Have you ever deliberately hurt yourself in some way, such as cut or hit yourself on purpose or taken an overdose?”

With response options: ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ 2 “How often do you self-harm?”

With response options: every day, several times a week, once a week, a few times a month, once a month, and several times a year

Appendix 3: Methodology

This report is informed by an analysis of data from the Health Behaviour in School Age Children Survey and through cross analysis of survey questions covering spanning individual, family, school and local community domains.

Further detail of the methodology for the HBSC study can be found in the England national reports www.hbscengland.com and the full external protocol is available from www.hbsc.org. The HBSC data is hierarchical and students are nested within classes, within schools as such to account for the hierarchical data structure. Multilevel

References

1

Brooks F, Magnusson J, Klemera E, Chester K, Spencer N, and Smeeton N. HBSC England National Report: Findings from the 2014 HBSC study for England. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire; 2015.

2 Hawton K, Saunders KEA, and O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012 379(9834): 2373-2382.

3 O’Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Miles J, and Hawton K. harm in adolescents: Self-report survey in schools in Scotland. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009 194(1); 68–72.

44

Fliege H, Lee JR, Grimm A, and Klapp BF. Risk factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009; 66(6): 477-493.

5

Hagell A. Adolescent self-harm. AYPH research summary No. 13. London: Association for Young People’s Health; 2013.

6

Kidger J, Heron J, Lewis G, Evans J, and Gunnell D. Adolescent self-harm and suicidal thoughts in the ALSPAC cohort: a self-report survey in England. BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12(69): 1-12.

7

Inchley J, and Currie D. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people's health and well-being. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children

(HBSC) study: international report from the 2013/2014 survey. Health policy for children and adolescents. WHO, 2016. (7)

8

Landstedt E, Gillander and Gadin K. Deliberate self-harm and associated factors in 17-year-old Swedish students. Scand J Public Health. 2011; 39 (1):17–25.

9

Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

10 Public Health England. How healthy behaviour supports children’s wellbeing [Internet]. 2013 [cited 15 Aug 16]. Available from:

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/232978/Smart_ Restart_280813_web.pdf

11

Moreno C, Sánchez-Queija I, Muñoz-Tinoco V, de Matos MG, Dallago L, Ter Bogt T,and Rivera F. Cross-national associations between parent and peer communication and psychological complaints. International Journal of Public Health. 2009; 54(2): 235-242.

12

Klemera E, Brooks F, Chester K, Magnusson J, Spencer N. Self-harm in Adolescence: Protective health assets in the family, school and community. The International Journal of Public Health (In press)

13

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/370686/HT_brief

ing_layoutvFINALvii.pdf 14

Ofsted. Not yet good enough: personal, social, health and economic education in schools [Internet]. 2013 [cited 15 Aug 2016]. Available from:

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413178/Not_yet _good_enough_personal__social__health_and_economic_education_in_schools.pdf 15

Evidence briefing: PSHE education, pupil wellbeing and safety at school [Internet]. 2016 [cited 22 Aug 2016]. Available from: www.pshe-association.org.uk/curriculum-and-resources/resources/evidence-briefing-pshe-education-pupil-wellbeing

16